The Big Questions

We have all heard in Art Galleries …

‘Art is useless.’

You can’t really argue with this statement. The truth is that in the majority of cases art has no practical function at all, unlike a knife and fork. Art is intended to appeal to our senses, our emotions, thoughts and ideas. We could live our lives without art, but who would design our clothes, cars, buildings, shoes, toys, wallpaper and furniture etc. Imagine being in the Sistine Chapel of the Vatican looking up and seeing a bland white ceiling, rather than being awe-struck by Michelangelo’s sublime masterpiece. Imagine a world without Edvard Munch’s The Scream, any painting by Claude Monet, Rembrandt, Titian, Picasso, JMW Turner and Kandinsky to mention but a few. Art reflects and explores human emotions, feelings, actions our creativity and imagination and in many ways determines our visual culture. It would certainly be a dreary old world if art, in it’s many forms, did not exist.

‘It’s not worth it’

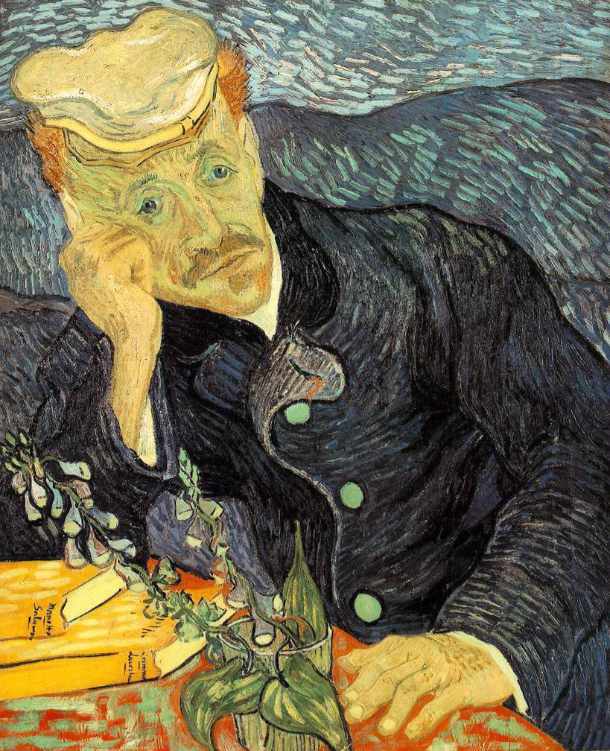

Cézanne‘s painting of The Card Players was bought by the Royal Family of Qatar in 2011 for $250m and Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi sold for $450m in 2017. But let’s look at another painting to perhaps explain why art works can command such ludicrous amounts of money. In 1990 Vincent van Gogh’s painting Portrait of Dr Gachet was sold for £44,378,696 ($75m), enough to build a small hospital or five or six schools. Some argued at the time that it was an obscene amount of money to pay for the work of a man mad enough to cut off his ear. If it sold today it would probably fetch three or four times that amount. Why? Firstly, the painting has no intrinsic value at all, other than the value of the canvas and paint, which is worth very little. It is only worth what someone will pay for it and someone thought it was worth millions.

So why did this person value the painting so highly? Simply because they were buying a unique piece of history. Van Gogh had created the work, touched it, felt it and expelled a great deal of emotion during its creation. From Van Gogh’s letters we know how he was feeling when he painted the picture, we know his innermost thoughts, his desperate plight and his continuous despair at his poverty and mental illness. Yet here was a man who could express his emotions through colour and paint like few others in the history of painting. When we stand in front of a Van Gogh painting we see Van Gogh himself, laid bare like a gossamer spider’s web, teetering on the edge of destruction, vulnerable to the slightest breeze. Like all great painters he can, through the medium of paint, show us the soul of humanity, it’s vulnerabilities, flaws and its assets.

‘Art is useless.’

You can’t really argue with this statement. The truth is that in the majority of cases art has no practical function at all, unlike a knife and fork. Art is intended to appeal to our senses, our emotions, thoughts and ideas. We could live our lives without art, but who would design our clothes, cars, buildings, shoes, toys, wallpaper and furniture etc. Imagine being in the Sistine Chapel of the Vatican looking up and seeing a bland white ceiling, rather than being awe-struck by Michelangelo’s sublime masterpiece. Imagine a world without Edvard Munch’s The Scream, any painting by Claude Monet, Rembrandt, Titian, Picasso, JMW Turner and Kandinsky to mention but a few. Art reflects and explores human emotions, feelings, actions our creativity and imagination and in many ways determines our visual culture. It would certainly be a dreary old world if art, in it’s many forms, did not exist.

‘It’s not worth it’

Cézanne’s painting of The Card Players was bought by the Royal Family of Qatar in 2011 for $250m and Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi sold for $450m in 2017. But let’s look at another painting to perhaps explain why art works can command such ludicrous amounts of money. In 1990 Vincent van Gogh’s painting Portrait of Dr Gachet was sold for £44,378,696 ($75m), enough to build a small hospital or five or six schools. Some argued at the time that it was an obscene amount of money to pay for the work of a man mad enough to cut off his ear. If it sold today it would probably fetch three or four times that amount. Why? Firstly, the painting has no intrinsic value at all, other than the value of the canvas and paint, which is worth very little. It is only worth what someone will pay for it and someone thought it was worth millions.

So why did this person value the painting so highly? Simply because they were buying a unique piece of history. Van Gogh had created the work, touched it, felt it and expelled a great deal of emotion during its creation. From Van Gogh’s letters we know how he was feeling when he painted the picture, we know his innermost thoughts, his desperate plight and his continuous despair at his poverty and mental illness. Yet here was a man who could express his emotions through colour and paint like few others in the history of painting. When we stand in front of a Van Gogh painting we see Van Gogh himself, laid bare like a gossamer spider’s web, teetering on the edge of destruction, vulnerable to the slightest breeze. Like all great painters he can, through the medium of paint, show us the soul of humanity, it’s vulnerabilities, flaws and its assets.

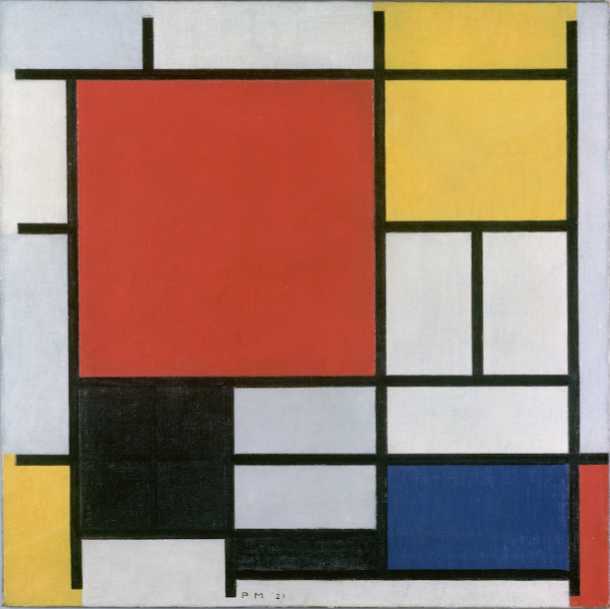

“The emotion of beauty is always obscured by the appearance of the object. Therefore, the object must be eliminated from the picture.”

Piet Mondrian

“With any medium you are working in, technical skills obviously help, but your mind is what you really need to expand. That is how you create work. That’s the role of the artist – to change the way you view things.”

Petra Collins

More Questions

It looks like a Photograph – that’s real Art!

Not necessarily. An artist might be technically brilliant and able to depict, for example, a person’s face with amazing accuracy, but is that all we want? We can admire the skill, but is the artist telling us anything about the person. If he isn’t then we are left with only the skill to admire and little else. We will probably pass the painting by and soon forget it. Like photography, too much emphasis on the technical aspects rather than the emotional, passionate and incisive insights can lead to a bland piece of work.

We need look no further than the marvellous portraits of Rembrandt van Rijn to see an artist who combines wonderful technical skill with the ability to capture emotion, feeling and pathos. This comes through because of his interaction with, and knowledge of the sitter, plus the ability to let these abstract concepts flow through his brush onto the canvas.

The technical skill argument is one that exercises most people who find modern art difficult to understand. This comes about primarily because they only use one means of judging the art, namely that the work has to look like something seen to be understood. By implication if the painting does not look ‘real’ the artist is dismissed as talentless or lacking in skill. Leonardo da Vinci could draw, using lots of lines, a naked woman with phenomenal accuracy and detail, where as Henri Matisse would often use just a few sweeping curves. Both are great draughtsmen, Leonardo’s work shows us the structure of the body of a woman with its accuracy, but Matisse shows us the sensuousness of the woman with his flowing lines.

Leonardo’s drawings could be described crudely as being as accurate as a photograph, whereas the Matisse is definitely not, yet they both give us insights into what it is that we understand by the concept woman.

Just to explain a little further, technical skill refers to the ability and mastery to create art using subject matter, mediums and technique. Whereas conceptual/abstract artists use paint or other materials to communicate ideas through their artworks. Their aim is to communicate ideas through the use of the right tools for their chosen medium such as paint, metal, etc. They don’t necessarily need technical skills in order to produce beautiful pieces of work.

It’s important to note that technical skill can be taught and learnt; however, artistic talent tends to come from within the individual—and that means it’s not something you can learn or be taught unless you have some innate ability.

And finally the ultimate criticism

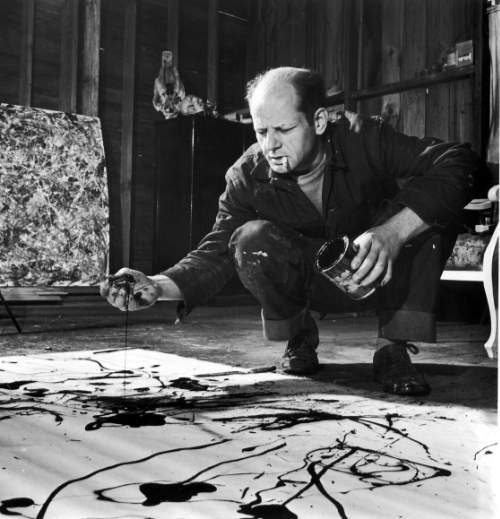

‘My five year old could do that!’

Put certain individuals in front of a painting by Jackson Pollock or Paul Klee and they will almost certainly utter the above phrase, or something very similar. But this says more about our own expectations and understanding of art than it does about the artist. Most of us expect to see objects we have seen before and can understand. When we are not given things we recognise we feel cheated and trapped, mired in our own tunnel vision, so we blame the messenger, the artist.

If we look at figurative art (art which represents nature or recognisable objects) it is superficially easy to make judgements based on comparisons with what we know, understand or have seen. When confronted with abstract art works we have no reference points on which to base our judgements. We are left with lines, colours and shapes ironically the very elements that figurative art depends on. The tendency is to dismiss the artwork because we cannot understand it in the way we think we can understand figurative art. Yet the most ‘realistic’ painting is no more than a series of colours, lines and shapes arranged on a flat surface, in a certain order, that happens to look like something we recognise.

What is really important is the artist’s ability to use colour, line, shape and texture in a meaningful way. Let’s see how this works. If we look at John Constable’s landscapes we admire them for their brilliant depictions of our natural world. This is because he uses colour, lines and shapes in a way that captures the essence of what nature is about. Similarly, certain abstract painters use colour, line and shape to appeal to our emotions and feelings, concepts we cannot see the way we see nature. They can be seen as creating a visual equivalent of an emotion or feeling, just as the naturalistic painter creates a visual equivalent of nature. It requires a greater effort on the part of the viewer to make the leap from the realism of the seen to the abstraction of inner feelings if a non- representational painting is to be comprehended.

We have seen that some abstract artists try to paint the visual equivalent of abstract concepts such as, balance, space, and floating for example. Imagine an artist trying to paint ‘love’ – remember we cannot see love, or touch it in a physical sense, but we can feel it. The artist might use certain colours and flowing shapes to represent visually the essence of what being in love might feel like. If on the other hand a representational artist chose to paint two people embracing and kissing each other this could imply love, but could also imply something quite different, like a farewell for instance. By using abstract means the artist tries to get to the essence of what love is rather than merely representing its manifestations. Which could be misinterpreted. Ah, I here you cry, the colours and shapes could also be misinterpreted. True, but isn’t that a true reflection of the abstract concept we refer to as love?

‘New needs need new techniques. And the modern artists have found new ways and new means of making their statements… the modern painter cannot express this age, the airplane, the atom bomb, the radio, in the old forms of the Renaissance or of any other past culture.’

Jackson Pollock

“A line is a dot that went for a walk.”

Paul Klee