Artist Profile

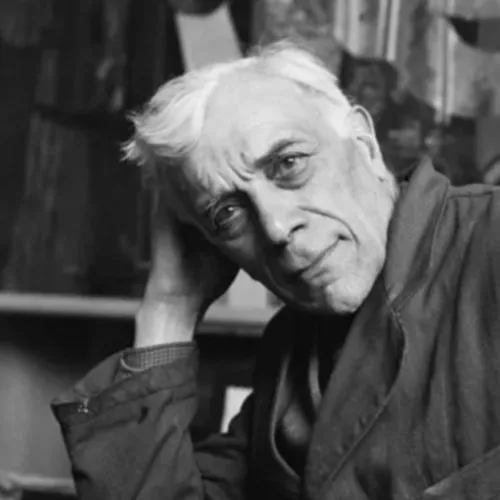

Georges Braque

Born – 13 May 1882 – Argenteuil, France

Died – 31 August 1963 – Paris, France

Artist Profile

Georges Braque

Born – 13 May 1882 – Argenteuil, France

Died – 31 August 1963 – Paris, France

Georges Braque was a French painter and sculptor, who, alongside with Pablo Picasso, co-founded Cubism and revolutionised art in the early 20th century. Braque’s work explored geometric forms, multiple perspectives, and the fusion of objects and space.

Georges Braque’s Early Life

Georges Braque was born on 13th May, 1882, in Argenteuil, near Paris, France, to parents Charles and Augustine. His father who was an amateur painter and his grandfather before him, managed a house decorating business, which is no doubt where Braque’s interest in texture and the tactile effects of paint came from. In 1890, the family moved to Le Havre, where Braque attended the local public school, and often accompanied his father on painting expeditions. He developed an interest in sports, especially boxing, and also learned to play the flute. At the age of 15, Braque enrolled in an evening art course at the École des Beaux-Arts in Le Havre where he studied painting and learned traditional painting techniques. In 1899, at the age of seventeen, he moved from Argenteuil to Paris, accompanied by friends Othon Friesz and Raoul Dufy.

Braque’s move to Paris

In Paris he completed his apprenticeship as a decorator and was awarded his certificate of competence in 1902. Between 1902 and 1904 with funding from his parents, he attended the Académie Humbert. Braque enjoyed the lax nature of the classes at the Académie which gave him the opportunity to experiment and more or less do whatever he wished, artistically. Together with fellow artist Francis Picabia he developed an interest in Impressionism, particularly the work of Alfred Sisley.

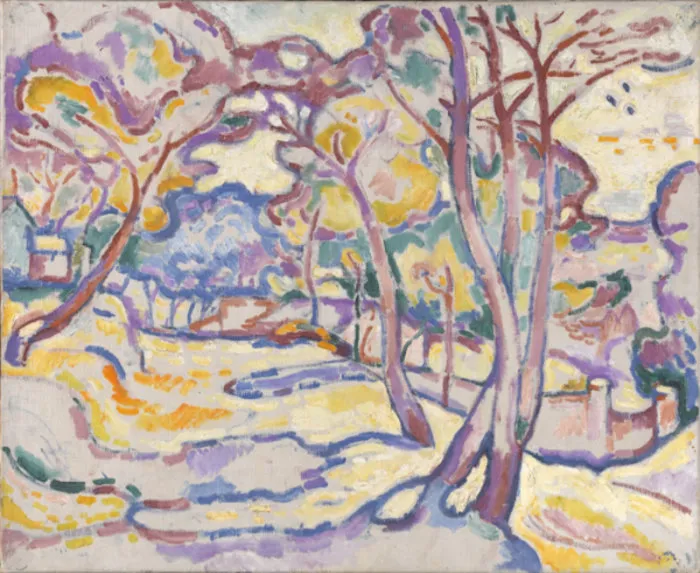

The Impact of the Fauves

But in 1905, he visited the Salon d’Automne in Paris and saw the violent explosion of arbitrary colour in the room occupied by the paintings of Henri Matisse, André Derain and others of the group nicknamed Les Fauves, the Wild Beasts. As a consequence Braque, who worked closely with Raoul Dufy and Othon Friesz, developed a slightly more subdued, version of the Fauvist style, but they did exploit the bold colour schemes and compositional structures seen in the paintings of Henri Matisse and others. In May 1906, Braque successfully exhibited his Fauve works in the Salon des Indépendants. But his work was beginning to change as he came under the strong influence of Paul Cézanne. Later in 1906, Braque travelled with Friesz to paint in L’Estaque, Antwerp in Belgium, and to the French Mediterranean coast near Marseille.

Braque meets Picasso

In 1907, Braque was introduced by Guillaume Apollinaire, the French poet and writer, to Pablo Picasso who invited him to visit his studio. Braque was profoundly affected by the visit, especially when he saw Picasso’s innovative work – Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. It soon became clear there was an immediate affinity between the two artists and an intimate friendship and artistic camaraderie soon followed. They collaborated closely, exchanging ideas almost daily and commenting on each other’s work. It is impossible to say which of the two was the principal inventor of this new revolutionary style of painting. Picasso provided, with his Les Demoiselles d’Avignon painting, the first liberating shock. But it was Braque, largely because of his admiration for Cézanne, who provided much of the early tendency toward geometric forms. Between them they developed the ideas that drove the development of this new artistic style. While their paintings shared many similarities at this time, in terms of their colour palette, style, and subject matter, Braque stated that unlike Picasso, his work was “devoid of iconological commentary” and was concerned purely with pictorial space and composition.

First Cubist Show

In May1908, Braque and Picasso exhibited their Cubist paintings for the first time at the Salon des Indépendants in Paris. Their work proved to be highly controversial and received mixed reviews from critics. By challenging conventional forms of representation, such as the use of perspective, which had been the rule since Renaissance Art, they had developed a new way of seeing and an art that reflected the modern age.

During the summer of 1908 Braque created paintings at l’Estaque, near Marseilles. They showed Braque’s determination to break imagery into dissected parts. The slab volumes, sober colouring, and warped perspective in his paintings from this period, are typical of the first part of what is now called the Analytical phase of Cubism. These radical works were rejected by the Salon d’Automne, but in the autumn of 1908 Braque showed his paintings at the Kahnweiler Gallery in Paris which prompted the Paris art critic Louis Vauxcelles to make his remark about “cubes” which would give this style of painting its name.

Braque works closely with Picasso

From 1909 onwards Braque worked closely alongside Picasso continually developing Cubism, but Braque’s work gradually began to develop its own distinctive style, which tended to combine elements of still life and landscape. Whereas Picasso’s work often explored the relationship between figures and various objects such as guitars. In 1911, Braque and Picasso spent the summer together in the French Pyrenees painting side by side. They produced works that were virtually impossible to distinguish from each other in terms of style and were reaching the pinnacle of Analytical Cubism. Traditional perspective had been completely eliminated, resulting in canvases whose subjects were so broken apart that it was almost impossible to perceive them. This formal breakdown of forms and space, coupled with a shockingly subdued palette, created an almost abstract art unlike anything seen before in the history of painting.

In 1911 Picasso introduced Braque to the model Marcelle Lapré. They soon fell in love and were married the following year. Soon after they moved to the small town of Sorgues, near Avignon in south-eastern France.

Synthetic Cubism

It was in 1912, that Braque and Picasso developed Cubism further into what is now known as its Synthetic stage. Subject matter became more central, more important and less with less emphasis on contrasting planes. They explored new techniques such as collage and incorporated letters, newspaper and even playing cards into their work. It was during this year, that Braque created what is generally considered the first paper collage by attaching three pieces of wallpaper to the drawing Fruit Dish and Glass. He also began to mix sand and sawdust with his paint to create textural effects on his canvases. These ideas began to suggest the idea that a picture is not an illusionistic representation, but rather an autonomous object in its own right.

War brings Tragedy

At the start of World War I in 1914, Braque served in the French army and was decorated twice that year for bravery. But in 1915 he suffered a serious head wound, which required a trepanation to cure and resulted in several months in the hospital, and a long period of convalescence at his home in Sorgues. During his recovery, he began making notes and observations alongside his drawings. In 1917 a collection of these notes were assembled by his friend the poet Pierre Reverdy, and published in the review Nord–Sud as “Thoughts and Reflections on Painting.”

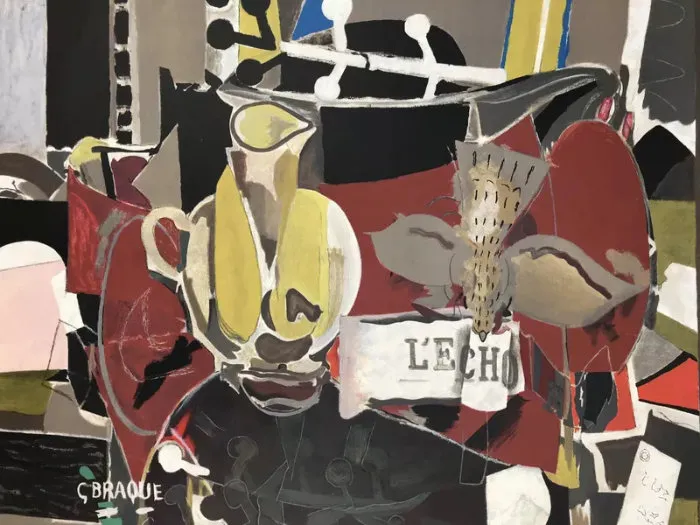

The Break with Picasso

It 1917 he was released from further military service and began painting again in the pre-war synthetic cubist style, but he never worked with Picasso again. The following year he began to collaborate with his friend Juan Gris, the Spanish-born Cubist painter whose paintings were also strongly Synthetic Cubist. But it wasn’t long before Braque began to move away from the strictures of the austere geometry of Cubism towards looser drawing and freer brushwork, as can be seen in this painting Still Life with Playing Cards. From this point onwards Braque’s work ceased to evolve in the methodical way it had done during the successive phases of Cubism before World War I. Instead Braque’s work developed into a series of personal interpretations based on the stylistic possibilities that Cubism had suggested.

Prosperity and Recognition

By the early 1920s, Braque was a prosperous, established modern painter who had become part of the well-to-do, cultured circles of post-war French society. He worked most of the time in Paris, in his studio in Montmartre and later in 1922, in Montparnasse. Also in 1922 he had a successful solo exhibition in Paris which not only brought attention to his own work but showcased his developments in terms of colour and collage.

From 1922 to about 1926, Braque’s work became more representational. He painted a series of paintings based around the idea of ancient Greek maidens carrying baskets of sacred objects to be used at feasts for the gods. Another series explored the idea of fireplaces and mantelpieces laden with fruit and sometimes guitars. In 1925, Braque painted “Fruit on a Table-cloth with a Fruit Dish,” which commemorated a banquet which had been held in his honour when he had returned from the war. The painting shows a table display flattened out in the pictorial plane, replicating the texture of wood and marble and shading the fruit.

New Beginnings

Also in 1925 Braque moved into a new house on the Left Bank in Paris designed for him by the modern architect, Auguste Perret. And later that year he received a commission from Serge Diaghilev, the great ballet impresario, to design stage sets for the Ballet Russe.

In 1931, Braque began creating white drawings over a background of black painted plaster, much like the Greek art he admired a few years earlier. Also in 1931, Braque received the Legion of Honour, a prestigious award from the French government, for his contributions to art. Later in the 1930s, he began a series of figure paintings examples being “Le Duo” and “The Painter and His Model.” Unlike his contemporaries Picasso and Matisse, Braque had abandoned working from a live model. His paintings therefore, are imaginary and the goaty bearded painter depicted in this work bears no physical resemblance to Braque himself.

In 1937 Braque won the first prize $1000 at the Carnegie Awards in New York for his painting, ‘The Yellow Napkin’.

World War II

The grim events leading up to the Second World War had a profound effect on Braque and during this period skulls often appear in his still life paintings. Works from this time appear to exude a sense of darkness, despair, agony and misery, and seem to make political statements. The painting ‘Baluster and Skull’ is a fine example, where colours replicate the complex emotions and reactions to impeding war.

Braque lived in Paris during World War II but continued exploring still life themes with sombre colour schemes despite the difficult conditions around him.

After the war, Braque resumed his practice of executing a series of paintings on a single subject or theme, such as birds, landscapes, and scenes of the sea.

The Series Paintings

Between 1948-1955 he produced a series of nine canvases, entitled “Atelier” or “Studio,” depicting imagery which sought to represent the artist’s inner thoughts about particular objects. The bird symbol frequently appears in these and later works usually as a metaphor for freedom and space. The paintings often depicted a picture within a picture and were altogether more personal, decorative and richly coloured than his pre-war paintings.

In 1948, he won first prize at the Venice Biennale and had his first retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1949 and the Tate Gallery in London in 1956.

In 1949 he was asked to paint panels for the ceiling of the Henri II room in the prestigious Louvre Museum in Paris. The ceiling is very ornate and posed significant design issues. He solved the problem by using the imagery of birds painted in basic flat colours that give the designs a powerful simplicity.

Stained Glass Windows

In 1956, his design for a stained-glass window for the church of Saint-Valery de Varengeville-sur-Mer, on the theme of the Tree of Jesse was installed. That year he was also awarded the Grand Prize for painting at the Venice Biennale, one of the most prestigious awards in the art world.

In the early 1960’s he designed three stained-glass windows and gifted them to the Chapel Saint-Dominique also in Varengeville.

In 1961, on the occasion of his eightieth birthday, his studio was taken down and rebuilt in its entirety in the Louvre’s Mollien Gallery, a previously unheard-of honour for a living artist.

Georges Braque’s Legacy

Georges Braque died on 31st August, 1963, in his studio home on the Left Bank in Paris. He was 81 years old. He was buried in the graveyard of Saint-Valery de Varengeville-sur-Mer which overlooks the English Channel.

Georges Braque was a quiet introvert, extremely observant, sharp, determined, and a very intelligent man. His contribution to art, particularly his role in the development of Cubism, was profound as was his innovative use of materials and techniques, as well as his willingness to challenge traditional ideas about art. His achievements made him one of most influential artists of the 20th century.

RELATED VIDEOS

Picasso

Cezanne

Artwork

Leave A Comment