3rd Element of Art: Context

Understanding context concerns the circumstances: time, place, political climate, social attitudes etc. in which the work of art was produced. Once again, we can subdivide context into three main categories namely;

- The Artist.

- The prevailing Political, Economic, Social or Religious Climate and Reception.

- Then and Now.

The Artist

In this section about understanding context we need to consider the artist’s attitudes, beliefs, interests, and values, as well as his education, training and life history. We might also try to find out something about his psychological state if that is possible. All these factors will influence how the artist produces his work. Vincent van Gogh was an artist who was essentially self-taught and had to cope with medical health problems, personal rejection and extreme poverty. It is not surprising that his work is often considered to be auto-biographical, in the sense that even his still-life’s seem to reflect his inner torment. His painting The Irises, completed in May 1890 is a typical example on this.

In contrast Edouard Manet, the French Impressionist painter, was the son of a senior civil servant and inherited a vast fortune from his father when just thirty years old. His upper-middle class background was important, because although he can be seen as a rebel – see his painting Olympia 1863 or Dejeuner sur l’herbe 1863 – he was actually a rather conservative individual who always sought traditional honours. Unlike Van Gogh he could afford to paint whatever he wanted to. By and large, he chose to reflect middle-class society in his paintings, yet his work often challenged that society both on moral and artistic grounds.

We should consider the artist’s intentions and purposes, but be careful as it can become a mind field of assumptions. In the vast majority of cases we have no idea what the artist really intended in a painting, unless there is firm documentary evidence. We can make an educated guess based on some of the issues we have previously considered and our knowledge of the artist and his life. But it remains an educated guess without evidence. An example, of how dubious assumptions can be in art appreciation is best illustrated by the following example.

Numerous art critics point to Picasso’s depression and poverty as the reasons behind his Blue Period paintings of around 1905, yet years later, during an interview, Picasso remarked that the reason for the Blue Period paintings was ‘because I could only afford to buy blue paint’! Was Picasso joking, or was he serious, who really knows?

The prevailing Political, Economic, Social or Religious Climate

Understanding context, the political, economic, social or religious climate in which an artist worked often has a profound effect on what he/she produces. For example, artists working in Nazi Germany during the 1930’s/40’s had to follow the strict guidelines laid down by the Nazi party. Those that complied worked in the style of a Social Realism, restricted to a form of figurative painting that glorified the Fatherland and the superiority of the German people above all others. Artists such as Emil Nolde and many others who chose not to follow this ideology were declared degenerate and in some cases persecuted. Most of these artists chose to leave and emigrate, primarily to the USA, where they established a strong foothold.

The artists who remained and followed the dictates of the Nazi Party produced work that today looks either bland or sinister, with its glorification of state controlled ideals. It is interesting to note the similarity between paintings produced under despotic regimes of both left and right.

In 1840’s France where the economic conditions for the poor were dire, some artists, notably Gustave Courbet chose to fight their cause. His Trilogy of Realism of 1848 is a prime example. The paintings, which emphasised the social conditions of the poor were initially displayed in the Louvre in 1850 until Emperor Napoleon III demanded their removal. These works formed the basis of Courbet’s Realist painting that was built on strong socialist principles and quite at variance to the prevailing political climate. It took an artist of very strong conviction (and massive ego) to produce work of this type given the political conditions of the time. We see these works today as important statements of social realism; a 19th century version of what you see is what you get.

Between the 13th and 19th centuries Christianity became the predominant power in Europe and it shaped European culture profoundly. Religious paintings often became objects of devotion, based on biblical texts, commentaries, and apocryphal stories. Christianity inspired artists to create works that tried to put into visual terms the nature of Christian mysteries. Through painting and other art forms religion utilized the beauty art to promote its message.

Reception Then and Now

The view of the society existing at the time a painting was produced is an important consideration when making judgements. Over time views and attitudes change. What was regarded as cutting edge and the height of fashion in one decade, can seem dated and old fashioned in another. Yet some art seems to transcend time and fashion and seems as relevant today as it did when it was produced. Edvard Munch’s Scream, Picasso’s Guernica, Leonardo’s Mona Lisa are timeless images. Probably because they represent universal values which we as human beings can appreciate, no matter which era we happen to have been born in.

In contrast, paintings produced in Nazi Germany reflect not only the cultural values but also the propaganda of an age most of us would like to forget. Today, these paintings have little relevance to our views and society. They no longer ‘speak’ to us they way they presumably did to certain sections of German society in the 1930’s and 1940’s. They are an important record of the time in which they were produced. But also a record of how art can be diluted when it is state controlled, rather than individually inspired.

Attitudes and values change over time and this can have a profound effect on how we value the work of individual artists. Rembrandt’s work wasn’t fashionable in the 18th century, yet today Rembrandt is regarded as one of the world’s greatest artists. We now judge his art for what it is and place less emphasis on the whims of fashion.

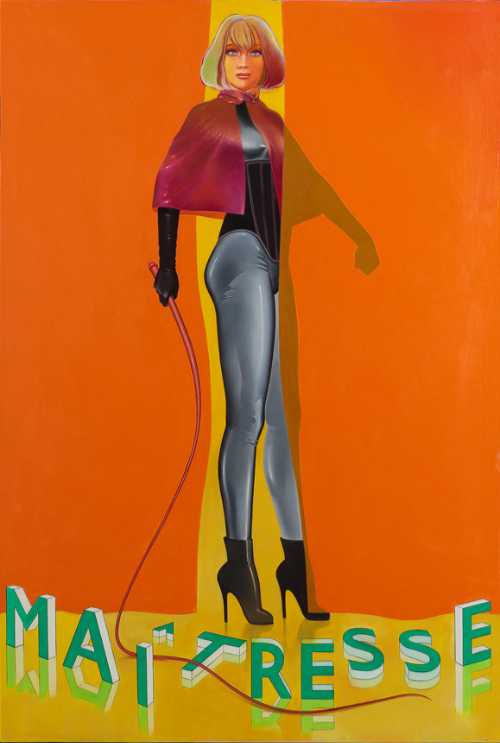

Changes of attitude has had a profound effect on the work of the British Pop artist, Allen Jones. His simple figurative imagery which often includes highly erotic symbolism such as fetishism, women in extremely high heels and body-clinging garments was popular in the ‘swinging sixties’, but has constantly been attacked by feminist groups ever since. Whether attitudes to his work will change again in the distant future, who knows.

On another level, we must not allow the lens of our own experience, attitudes and prejudices colour our judgement. We have to try to be open minded when looking at art. Compare the work of John Constable and Damien Hirst. It is crucial to understand the context in which the two artists were working, as it was radically different. Constable was immersed in rural life, painting images that evoke landscape in such a way we can almost feel it. Hirst, on the other hand, is trying to shock us out of what he sees as our complacency. His imagery is intended to make us reconsider our attitudes to smoking or our treatment of animals. If we can turn a cow into beef burgers what is the problem with turning it into an art work? Today we regard Constable as a great landscape painter. But, in the 19th century he struggled to get recognition, partly because of the hierarchy of genres. He was a mere Landscape painter, not nearly as important as a History painter. Damien Hirst is the enfant terrible of British art; he is very successful and commands high fees for his work. It will be interesting to see what the vagaries of time has on his reputation.