How the Bauhaus changed the world

What was the Bauhaus?

How the Bauhaus changed the world

What was the Bauhaus?

In the 19th century the English designer William Morris was one of the first to promote the idea of creating high-quality hand crafted objects whose design was influenced by its intended purpose. In England, by the end of 19th century, the Arts and Crafts movement were producing individually created luxury objects designed for every aspect of daily living.

The Bauhaus rejected the Arts and Crafts movement’s idea of individual creation in favour of machine production, thus making great design available for everyone. The Bauhaus idea fundamentally changed the course of art and design in the 20th century.

The Bauhaus

The First Phase

The Bauhaus was formed in 1919. The young architect, Walter Gropius combined two schools, the Weimar Academy of Arts and the Weimar School of Arts and Crafts, into what he called the Bauhaus, or “house of building.” Its manifesto proclaimed, “Let us create a new guild of craftsmen without the class-distinctions that raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist!”.

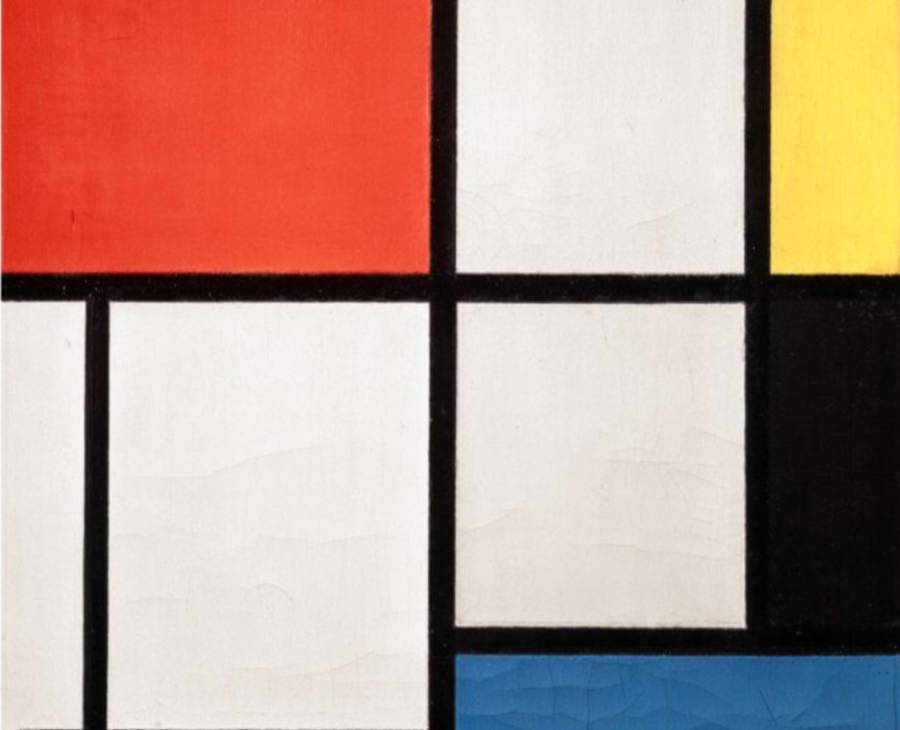

The roots of the Bauhaus can be linked to the Arts and Crafts Movement, via the Deutsche Werkbund. It took inspiration from medieval guilds, calling its teacher’s masters and journeymen. The Bauhaus teaching method began with a six-month foundation course. It was followed by simultaneous training in a craft by a craftsman. Then the investigation of the formal problems of art by an artist. Finally the study of architecture. Leading avant-garde artists such as Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky were brought in to guide the students. Early Bauhaus works were influenced by Expressionism and had a handcrafted appearance.

Second Phase

Due to a general shift in taste in the arts, the failure of the Bauhaus to fund itself by selling products, and the influence of Theo van Doesburg, who criticised the direction the school had taken, Walter Gropius altered the direction of the course to combine art and industry. He pronounced this in a lecture in 1923 – ‘Art and Technology: a New Unity!’. This coincided with the first exhibition of work at the Bauhaus, in a building owned by the school. It was furnished with products by students and staff. Carpets, tiles, radiators and lights were designed by Moholy-Nagy. These sat alongside furniture designed by students. Also included was Marcel Breuer‘s functional kitchen. The idea of which provided the basis of today’s fitted kitchens.

Third Phase

The Bauhaus had a strained relationship with the increasingly right wing Weimar Republic. But it was financial pressure that forced the school to close in 1925. An alternative location was found in Dessau, and funds provided to allow for a new building designed by Walter Gropius for students and staff. This building contained many ideas that later became hallmarks of modernist architecture.

The speed of construction was testament to the advantages of new materials and methods employed by Gropius. Structurally the building was an experiment. A reinforced concrete skeleton supported floors on beams, and flat roofs covered with new waterproof material. The building was completed in October 1926. At this point some graduates were taken on as staff. These ‘Young Masters’ had a different outlook to their older colleagues. A generation younger, at home in the studio or the workshop and teaching by example, they are seen as responsible for the identity of the early Dessau Bauhaus.

Fourth Phase

Gropius resigned in 1928, naming a Swiss architect, Hannes Meyer as successor. The curriculum now consisted of life-drawing, biology and philosophy. Students also learnt town planning, sociology, Marxist theory, physics, engineering, psychology and economics. Meyer also persuaded the workshops to produce mass-produced items. The most successful being wallpapers which are still available today. For the first time the school achieved its aim of mass produced quality items. But Meyer’s Communist leanings put him in conflict with the increasingly right-wing municipal government of Dessau and in 1930 he had to resign.

The architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe replaced him as director. He tried to free the school from politics, but met with opposition from left-wing students. On one occasion a political meeting developed into a riot. The school was cleared and those responsible expelled. On re-opening, students were told they would be expelled if the rules banning political activity were not followed. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe made the Bauhaus into a more traditional school of architecture, but courses in weaving, photography, and the fine arts survived.

The increasingly unstable political situation in Germany, combined with the perilous financial condition of the Bauhaus, caused Ludwig Mies van der Rohe to relocate the school to Berlin. In 1930, reopened on a much reduced scale. The Nazis thought the Bauhaus’ ‘international’ style was unpatriotic and eventually withheld the school’s grant and terminated all staff contracts. The school closed on September 30th 1932. In desperation, Mies rented and converted a disused Berlin telephone factory. But on the 11th April 1933, soon after Hitler came to power the police closed the school. Exactly 14 years after it opened.

The Bauhaus legacy endured because many of the teachers and key figures of the Bauhaus emigrated to the United States. There their work and their teaching philosophies influenced generations of young architects and designers. Marcel Breuer and Walter Gropius taught at Harvard. Josef and Anni Albers taught at Black Mountain College. Moholy-Nagy established the New Bauhaus in Chicago in 1937 and Mies van der Rohe taught at the Illinois Institute of Technology.