Artist Profile

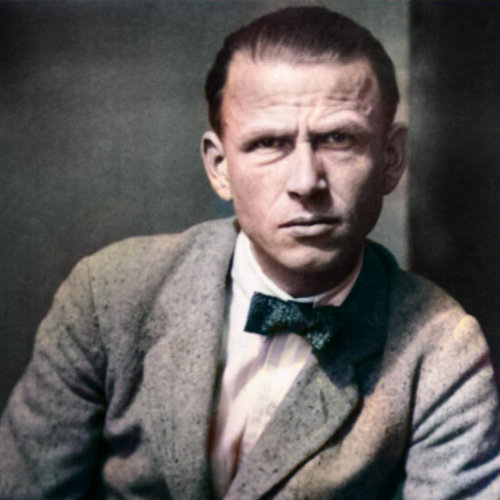

Otto Dix

Born – 2 December 1891 – Untermhaus, Germany

Died – 25 July 1969 – Singen, Germany

Artist Profile

Otto Dix

Born – 2 December 1891 – Untermhaus, Germany

Died – 25 July 1969 – Singen, Germany

Otto Dix was haunted by his experiences of the 1st World War which resulted in his harsh and brutal paintings of war and the Weimer society of the 1920’s. He later painted nudes and savagely satirical portraits of celebrities from Germany’s intellectual circles. A leading light of the Neue Sachlichkeit movement, he was later persecuted by the Nazi’s, but survived

Otto Dix: The life of an Artist – Watch NOW

Early Life

Wilhelm Heinrich Otto Dix was born on the 2nd of December 1891 in Untermhaus near Gera in Thuringia in Germany. He was the eldest son of Ernst Franz Dix who was a mould maker in an iron foundry, and his seamstress wife Pauline Louise. They were working-class parents, but his mother Louise enjoyed poetry and had a cousin Fritz Amann who was a painter. At the age of ten, Otto Dix modelled for Fritz Amann. He was so impressed by his experience in his studio, that he decided to become a painter himself. Fritz Amann would later become Dix’s mentor.

Otto Dix’s Art Education

Between 1899 to 1905 he attended an elementary school in Untermhaus. He was inspired by his art teacher Ernst Schunke, who guided his study and later helped him get financial assistance for further study at art school. From 1905 until 1909 he trained locally under the artist Carl Senff and began painting his first landscapes of Dresden and Thuringia in oil and pastel.

In 1909 Dix enrolled at the Dresden School of Arts and Crafts and attended classes there until 1914. Luckily, after the first term his fees were covered by a stipend. He made extra money by selling small portraits and genre paintings. He also coloured black and white photographs. The Academy being a more craft-oriented institution did not teach academic painting. As a result, Dix taught himself how to paint through an intensive study of the Old Dutch, Italian, and German Renaissance Masters. He analysed their methods and learnt, through lots of practice, how to build up layers of paint to create depth and luminescence. He also admired the German Expressionists, the Post-Impressionists and especially the work of Vincent van Gogh, whose work he saw in the Van Gogh exhibition in Dresden in 1913.

World War 1

At the start of the War in 1914 he voluntarily enlisted for military service and trained as a machine gunner in Dresden. From 1915 he served as a machine gunner and platoon leader on the frontlines in Flanders, Poland, Russia. And later in 1916 was at the Battle of the Somme, during the major allied offensive. Dix was wounded several times. On one occasion he nearly died when a shrapnel splinter hit him in the neck. “War” he said, “is so bestial: the hunger, the lice, the mud, those insane noises.” During 1916 he had his first exhibition of war drawings at the Galerie Arnold in Dresden.

Years later he recalled why he joined the army: “I had to experience how somebody beside me suddenly falls over and is dead and the bullet has hit him squarely. I have to experience all the ghastly, bottomless depths of life for myself; it’s for that reason I went to war.”

At the end of the war in 1918, he returned to Gera. Dix was profoundly affected by what he had experienced on the frontlines. He later described a recurring nightmare in which he crawled endlessly through a tunnel of destroyed houses. His traumatic experiences influenced many of his later works, which became increasingly political. Along with fellow German artist and friend George Grosz, he adopted left wing views and referred to himself as a “revolutionary pacifist”.

Dada and Trauma

In 1920 Otto Dix and George Grosz took part in the first DADA fair at the gallery Burchard in Berlin and later in the German Expressionists’ exhibition in Darmstadt. But Dix was angry, especially about the way wounded and disabled ex-soldiers were treated in Germany. This anger can be seen in his paintings; The War Cripples, The Prager Street and the Match Vendor.

Dix’s art became increasingly more morbid and realistic. In the painting ‘the Skat Players’ he created three World War I veterans. The devastating toll of war reduced the veterans to composites of human flesh and artificial body parts.

Dix’s work veered toward social satire, developing a grotesque and exaggerated aesthetic that along with George Grosz, Max Beckmann and others formed the basis of the Neue Sachlichkeit. The New Objectivity movement sought to represent the harsh social and political realities of the Weimar Republic. It was during this period he devoted himself to furthering his study of old master painting techniques. Initially drawing in egg tempera, followed by thin glazes of cold and warm tones in oil paint.

Otto Dix’s Painting are Confiscated

In 1923 he married Martha Koch, Dr. Hans Koch’s ex-wife. Later that year their daughter Nellie was born. Shortly afterwards his painting Salon 1 was confiscated in Darmstadt. It was regarded as shocking because it examined the life of women in the aftermath of war. Many, despite their age, had turned to prostitution in desperate attempts to earn money to feed themselves and their families. It was not his intention to shock, but simply to tell the truth. He wanted to ensure people would never forget the price paid by people when their governments took them to war.

In 1923 the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne bought Otto Dix’s painting, The Trench. It depicted dismembered and decomposed bodies of soldiers after a battle and caused such an uproar it had to be displayed behind a curtain. A critic described it as “perhaps the most powerful anti-war statement in modern art”. The strength of protests and criticism led to the painting being returned to Otto Dix in January 1925.

In 1925 Dix settled in Berlin where his work, like that of artist George Grosz—his fellow veteran—became increasingly critical of contemporary German society. It also dwelled on the act of Lustmord, or sexualized murder, by drawing attention to the bleaker side of life. To him everyday crime was the reflex to, and continuation of, the lunacy of war.

Dix’s iconic portrait of Sylvia von Harden

In 1926 he painted his iconic portrait of the journalist Sylvia von Harden. The painting came to characterise the period as much as the woman herself. It was referenced in the 1972 film Cabaret which was also set in the Weimar-era of 1920’s Berlin. Dix claimed Sylvia von Harden was a perfect image for a society that cared more about a woman’s psychological state than her outward appearance.

In 1927 he moved to 32 Bayreuther Strasse in Dresden. Later he was appointed professor of art at the Dresden Art Academy. On the 11th of March that year his son Ursus was born.

Metropolis

Otto Dix’s paintings were shown in the 16th Biennial in Venice and at the international exhibition of modern art in the Brooklyn Museum in New York in 1928. Shortly afterwards he began work on his great masterpiece, Metropolis. To understand this painting context is vital. Hyperinflation had taken hold and the economy of the Weimar Republic had been decimated due to reparation payments as a result of 1st World War. Consequently, the middle class was almost completely wiped out. Leaving just the extremely wealthy and the extremely poor. There was widespread unemployment, hunger, and malnutrition. Metropolis, shows the depravity of the situation the Weimar Republic faced in the 1920’s. In the centre panel Dix portrays the upper classes, they are partying, having a great time. Whilst just outside, people are starving, resorting to prostitution to fulfil their basic human needs. There desperation is clearly seen in the two side panels of the triptych. See the video for details.

In 1929 Dix exhibited in Paris and Detroit and began work on the War triptych whose centre panel is a reworking of the Trench painting of 1923. The War triptych is actually four panels which shows men going into battle, the aftermath of conflict, and the return from the battlefront. The painting, heavily influenced by his war experience, extreme sacrifice and apocalypse was mixed with the psychological influences of Friedrich Nietzsche and the Bible. It was completed in 1932.

Savagely Satirical Portraits

During the 1930’s Otto Dix was a committed portrait painter, at a time when photographic portraits had become much more fashionable. Dix commented, ‘Painting portraits is regarded by modernist artists as a lower artistic occupation; and yet it is one of the most exciting and difficult tasks for a painter.’ He produced a number of child portraits and many savagely satirical portraits of German intellectuals and leading lights of German society.

In 1931 Otto Dix became a full member of the Prussian Academy of the Arts in Berlin. He also took part in the German Painting and Sculpture Show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The following year he exhibited the War triptych at the Prussian Academy and produced a mural for the Museum of Hygiene in Dresden. This was later chiselled off the wall by the Nazis in 1934.

The Nazi’s confiscate his Paintings

When Hitler and the Nazis came to power in 1933, Dix was dismissed from his professorship at the Dresden Art Academy. Apparently, through his painting, he had committed a ‘violation of the moral sensibilities and subversion of the militant spirit of the German people’. His students were also reprimanded. Later that year a number of his paintings were ridiculed in the Nazi Art exhibition, ‘Reflections of Decay’ held in Dresden.

In 1934 the Nazis banned the Otto Dix from exhibiting his work. But he did take part in the German Painting exhibition in Zurich in 1935. In 1936 he moved to Hemmenhofen on the shore of Lake Constance very close to the Swiss border. He lived there for the rest of his life.

In 1937 Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Propaganda Minister ordered the President of the Reich Chamber of Visual Arts, Professor Ziegler to confiscate 260 of Otto Dix’s paintings. In July 1937 8 of Dix’s paintings, including The War Cripples, were exhibited at the infamous Degenerate Art Exhibition in Munich. At the time Otto Dix, like all German artists, were forced to join the Nazi government’s Reich Chamber of Fine Arts. Membership dictated that Otto Dix had to promise to paint only inoffensive landscapes or portraits. He he didn’t always comply.

Arrested by the Nazi’s

In 1939 Otto Dix was arrested by the Gestapo and locked up for two weeks in Dresden. Allegedly he was complicit in the Munich attack on Hitler’s life. When he was released, he took refuge on the Höri peninsula, on the shores of Lake Constance. It was just a stone’s throw from the Swiss Border. On the 20th of March 1939 Hitler ordered the Berlin Fire Department to burn almost 5000 art works including paintings by Otto Dix, Rene Magritte and many others. Thousands of other works by major artists were also confiscated. They were sent to Zurich and Lucerne in Switzerland to be auctioned off to fill the Nazi coffers.

Rather bravely in 1942 Otto Dix turned down a contract to paint the portrait of Joachim Von Ribbentrop, the foreign minister of the German Reich. Towards the end of the war in 1945 Dix was forced to enlist in the German People’s Militia “Volkssturm”. He was sent to the banks of the Rhine in March 1945. The following month he was captured and taken prisoner by French forces and placed in a prison camp in Colmar, north eastern France. Luckily, the commandant recognized who he was and allowed him to paint in the camp workshops. He completed a triptych for the prison camp Chapel. He was released in early 1946.

A Different Direction

After his release he returned to live in Hemmenhofen and his indomitable spirit began to return. His painting took a new direction producing works on religious themes such as ‘Job’ and ‘Christ on the Cross’.

In 1948 he participated in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern art in New York and in numerous exhibitions in East and West Germany. Otto Dix was very unusual in his ability to negotiate between the regimes of West and East Germany. Travel between the two does not seem to have been much of a problem for him, when for others it was banned. In 1955 he became a member of the German Academy of the Arts in West Berlin. The following year a member of the German Academy of the Arts in East Berlin. He received major awards in both the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic.

In 1959 he travelled to southern Italy and later created the mural ‘War and Peace’ for the town hall of Singen in Baden-Württemberg. It is the only surviving Otto Dix mural.

Otto Dix – The Final Years

Later in 1966 he paid his last visit to Dresden and received numerous honours in both East and West Germany to commemorate his 75th birthday. In 1967 Otto Dix travelled to Greece but later in November of that year he suffered his first stroke which resulted in his left hand being paralysed.

Otto Dix became an honorary member of the Karlsruhe Art Academy in 1968. He also received the Rembrandt prize from the Salzburg Goethe Foundation. Later the same year his triptych painting War was purchased by the state art collection in Dresden.

Dix donated a number of drawings and a collection of copperplate engravings to the Dresden Art Gallery in 1969. On the 19th of July of the same year, he suffered his second stroke. 6 days later he died of a heart attack at the age of 78 in the hospital in Singen. He was buried on the 28th of July in the cemetery at Hemmenhofen.

The Legacy of Otto Dix

Otto Dix constructed his paintings as though staging the world as a play. His sharp-eyed representation, his early obsession with injured veterans and his use of parody, suggest a resignation and acceptance of life’s trials and tribulations. But he is perhaps best known for his portraits that came to symbolise the hedonistic Weimar Republic of the 1920’s. He influenced many portrait artists throughout the 20th century.

Best Auction Price

The best price paid for a painting by Otto Dix was $6,010,929 for his ‘Portrait of the Lawyer Dr. Fritz Glaser‘, sold at Sotheby’s, London in 1999.

Artwork

Leave A Comment