The story behind the painting

Sunday Afternoon on the Grande Jatte

The story behind the painting

Sunday Afternoon on the Grande Jatte

Georges Seurat painted ‘A Sunday on the Grande Jatte’ in Paris in 1884. This French Impressionist painting is painted in oil on canvas, and is more than 2 metres by three metres in size.

Georges Seurat

Georges Seurat was born in 1859 into a comfortable bourgeoisie family in Paris. He trained at the Ecole des Beaux Arts which he entered at the age of 19. He meticulously studied great painters of the past such as Raphael and Poussin, but in 1879 military service interrupted his studies.

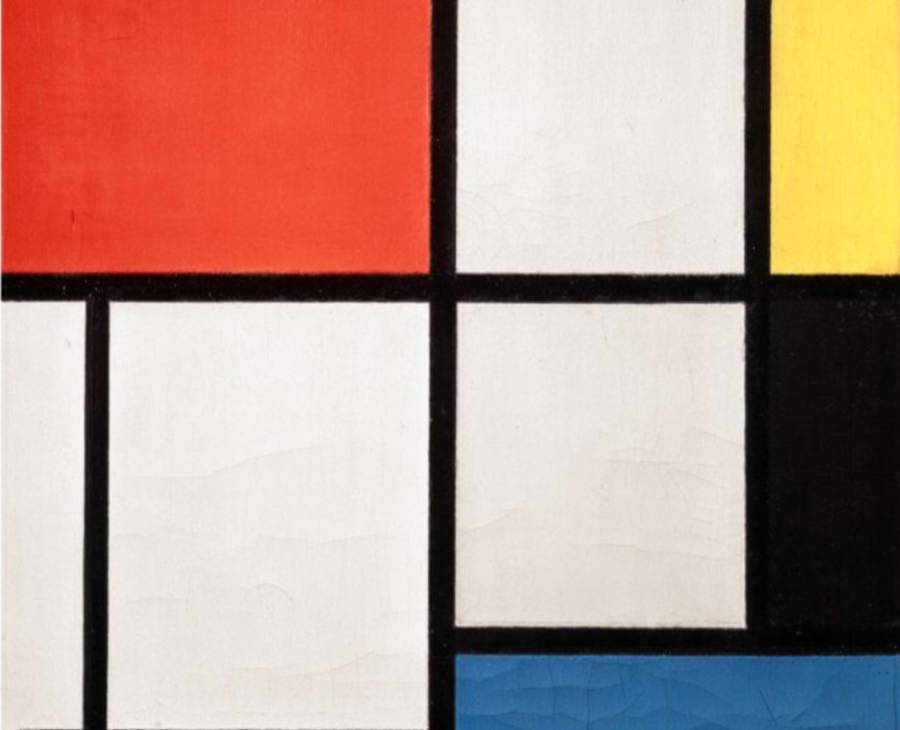

A shy person, he was driven by a love of theories which resulted in him creating the style of painting he called Divisionism. Divisionism (better known as Pointillism) is a way of painting in which colour effects are created by applying small areas of pure colour onto the canvas side by side. From a distance the eye mixes the colours. By placing dots of yellow and blue close together the eye will mix them and see green.

Unfortunately, Seurat made extensive use of Zinc Yellow which was a very bright and pure yellow. He used it extensively in his painting, ‘A Sunday on the Grande Jatte’. However, within 15 years the colour started to change from a bright yellow to a dull ochre brown. The picture we see today is much duller than was originally intended. Divisionism was a great theory, but not so successful in practise.

Painting The Grande Jatte

Georges Seurat began his painting, ‘A Sunday on the Grande Jatte’ in 1884 at the age of 26 completing it two years later. Seurat made many visits to the Grande Jatte completing numerous drawings which formed the basis of his painting. The Grande Jatte itself is a small island in the river Seine situated to the west of Paris. It was popular because well-to-do Parisians used it for recreation on Sundays. It was definitely a place in which to be seen.

Seurat’s completed painting was first exhibited in May 1886 at the Maison Dorée in Paris. Later that year it was included in the Salon des Independents, again in Paris. Tragically, Georges Seurat died of meningitis aged just 31 in 1891. Later that year his painting, ‘A Sunday on the Grande Jatte’ was sold for 800 francs. It was sold again in 1924 to Frederic Clay of Chicago and given to the Art Institute of Chicago in 1926.

The Critics did not like the Painting

Although Georges Seurat embraced the modern ideas of artists such as Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir. Capturing the accidental and instantaneous qualities of light in nature was not enough. Georges Seurat was attracted to the art of ancient Egyptian art and Italian Renaissance frescoes. As he said, ’I want to make modern people, in their essential traits, move about as they do on those frescoes.’

Contemporary critics were less than complimentary about the idea and the painting. ‘Bedlam’, ‘Scandal’ and ‘Hilarity’ were just a few of the terms used to describe it. Critics found the figures in the painting to be less a reflection of earlier artistic styles and more a commentary on the artificiality of modern Parisian society.

What makes this a Great Painting

Georges Seurat was not trying to give us a real picture of Parisians at play on a warm Sunday on the Grand Jatte. The painting is more a reflection of his own personality and especially the importance of painting technique, colour theory and compositional qualities.

Many of the figures in the painting are seen in profile, reflecting his study of ancient Egyptian bas relief sculptures. The figures look static and timeless, as they do in many of Poussin’s classical landscapes. No one is moving, perhaps reflecting the boredom of stilted conversations on a hot Sunday afternoon. But if you look carefully, there is movement. The young girl is running, her hair flowing in the wind. The small dog bounds towards the larger dog and fluttering butterflies provide a little chaos in the tranquillity.

In the bottom left of the painting we see that the Grand Jatte was not just for the well-off middle classes. There is a rough looking oarsman smoking his pipe. Lounging on the grass alongside him lies the middle-class lady with her fan. She has carelessly discarded it on the ground behind him. The ‘Toff’ with his top hat and cane also sits nearby. Above the ‘Toff’ are two women fishing, not a pastime middle class lady of the time would normally indulge in. These women have been identified as prostitutes. Fishing was merely a metaphor for their real objective, their potential catches being the two soldiers about to stroll their way.

All is not what it seems

Notice that the majority of men and women are dressed in the height of 1880’s fashion. The ladies sporting nipped in waists, bustles and carry elegant parasols. The men stand sartorially with their top hats and canes. But not all is what it seems. Notice a Capuchin monkey which, unfortunately, were regarded as fashionable pets amongst wealthy Parisians in the 1880’s.

Some critics suggest the monkey represents something quite different. Implying that the woman holding the leash of the monkey, is a prostitute. Feigning middle class respectability, whilst standing with her probably married companion. This is a veiled comment about the hypocrisy of French society in the 19th century.

Seurat’s meticulous approach to painting can also be seen in the painted frame. It has been designed so the frame contains the exact complementary colours to the colours next to the frame in the painting.

Finally, notice the couple on the right of the painting look far too big and there is a slight oddness to the perspective? This is deliberate and a result of Georges Seurat’s obsessive nature and his preoccupation with geometric perspective. The 23 preparatory drawings he completed for this painting created a very interesting idea. Seurat worked out the perspective so the painting should be viewed from an angle. If you stand at 45 degrees to the right of the painting, all distortions disappear, the figures look in the right proportions to one another. The result of a very clever mind indeed. Check out the video to see how this works.