2nd Element of Art: Content

Over the years Art historians have used a number of terms to describe Content; Subject Matter, Meaning, or Significance. They are all basically the same thing i.e. what message is the painting /art work providing. There are two ways of understanding content, the traditional and the more modern approach.

The traditional approach relies on sorting content in regard to its iconography -the term artists use for the language of images. Namely the signs, symbols and conventions used to determine what content is being displayed in the painting. The type of content in a picture is called its genre. For example, a painting depicting a famous victory in battle, heroic soldiers, dark turbulent skies, death, destruction and ultimate victory etc., would be classified in the History genre. A painting of rolling hills, trees, cottages with a few minor figures, animals etc would be the Landscape genre. The genres had an hierarchy hence a History painter such as JMW Turner was held in higher regard that John Constable who was a Landscape painter. If you were a mere Still Life painter then you were at the bottom of the pile.

Let’s look at a more modern approach to understanding content, which is to split content into three categories as we did with the first Element of Art, Form, namely:

- What you see

- What you understand

- Considering the Elements of Art (Form, Content, Context) together to come to a conclusion about the work.

What You See

This is the easy bit. First we start with what we can deduce from the painting based on what we know. Unlike the traditional approach there is no hierarchy here. What you See simply means looking at the painting and describing what is seen.

For example, we might see a balding man standing in a room in front of an elaborate cabinet. He is wearing military uniform on which medals are pinned. He is obviously from a past age. Our appreciation of the painting is based purely on what we can describe and is seen in the painting. Remember here we are just concentrating on the content of the painting, not the other elements we looked at under Form. This is the point many people walk on to the next art work. Others, who realise the man is Napoleon will move on to What You Understand and a deeper understanding.

What You Understand

As we can see the move from What You See to What You Understand understanding content requires a certain level of knowledge, the knowledge to recognise the fact that the man in the painting is Napoleon.

Other elements that would add to our knowledge in this area are an understanding of the symbols that are often used by artists to tell the story of the painting. There are many symbols that an artist could use, so just a few are listed here:

- A skull shown next to an egg timer can symbolise that humans are mortal and sometime in the future their lives will end.

- A red rose often signifies martyrdom, a white rose purity. They are often seen being held by the young Christ or the Virgin Mary.

- Goats often signify lust. In mythological paintings figures with hairy legs or hooves or goat-like features can be seen as lustful.

- An egg always symbolises rebirth, hence the link with Easter.

As we can see from the few examples above once we understand something about the symbols and signs – effectively the ‘words of art’ we have a better chance to understand the ‘language’ of the painting. Let’s start by looking at some of the most obvious signs and symbols you might encounter in painting.

Signs and Symbols

Common Signs

Understanding content is easiest with these familiar signs. They are so common everyone understands them. We have all seen pictures of Winston Churchill giving the ‘V’ for victory sign. In the UK we all know what the sign means when the hand is turned the other way around. Every child has at some time played at being a pirate and the skull and cross bones flag becomes an essential sign in the game.

Similarly, we know we are on a motorway when the traffic signs become blue. We cannot enter a road if we see a red circular sign with a red line across. We react almost instinctively to these signs, their meaning is instantly clear. These signs give us vital pieces of information about how we should respond in a given situation, incident or when view a work of art. Common signs appear in lots of painting and are there to give us insights into what the painting might mean.

Symbols of attribution

These are symbols or objects, which an individual might hold or be associated with which identifies who the person might be. The young child holding a bowl of water in the painting Christ in the House of his Parents 1849 by John Everett Millais is identified as John the Baptist. This is because he is holding a bowl of water. The context of this painting is an important factor. We have to understand that this is a religious painting, otherwise the young boy holding a bowl of water could not be identified.

Similarly in the same picture, the young Christ is identified by the cut on the palm of his hand and the drop of blood that has fallen onto his foot. Obvious signs of stigmata /crucifixion. Other more specific examples are; a small child holding a bow and arrow becomes cupid, or a female saint with a wheel is St Catherine. This is because of the wheel that bears her name and on which she was almost crucified.

If we can identify the symbols of attribution in a painting, we have clues to identifying the individuals.

Abstract Figures

Understanding content in art can be difficult when we see figures in paintings that cannot be clearly identified as above, their personalities are obscure. These figures often represent abstract ideas or values in the painting. Examples are:[1]

- Truth – A naked female holding a peach with single leaf, a sun or a mirror. She may also have her foot on a globe.

- Ignorance – A fat, unpleasant woman or hermaphrodite usually blindfolded or with no eyes, may also wear a crown.

- Innocence – a young girl holding a lamb, or maybe she is shown washing her hands

[1] For a comprehensive list of abstract figures, symbols and their meanings see A.R.T. by Robert Cumming

Allegories

These are stories in which individuals, events or objects are used to convey the meaning of the work. Allegories are probably the most difficult to decipher. They should not be taken on face value, because allegories are awash with hidden meanings, cross-references and deliberately obscure puzzles set by the artist. It is almost as though the artist is playing an intellectual game with the viewer.

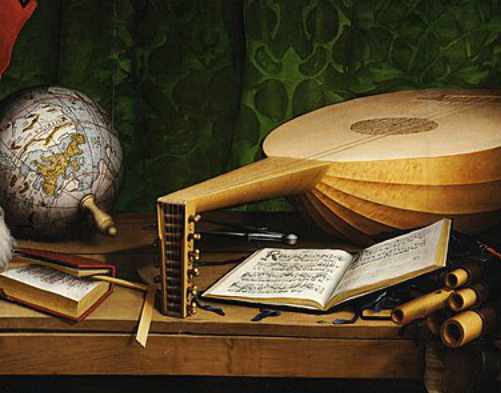

A good example of an allegorical painting is The Ambassadors 1533 by Hans Holbein The Younger. Deciphering the symbols gives us insights into the paintings real meaning.

The Ambassador on the left is Jean de Dinteville who commissioned the painting, together with his friend, George de Selve. They visited England in 1533 as ambassadors of Francis I to the Court of Henry VIII.

The Symbols:

Inscribed Dagger: Dinteville holds a dagger inscribed in abbreviated Latin that gives his age as 29.

Globe: The globe shows the countries important to Dinteville and even depicts his own chateau at Polisy near Troyes.

Arithmetic Book: is a new publication on applied mathematics and is held open by the set square. It symbolises the breadth and modernity of the Ambassador’s education.

Skull: casts a shadow of death across the floor and tells us that Dinteville was in poor health. You will notice a skull as an insignia on his cap.

Mosaic Pattern: this is an exact copy of the pattern on the floor of Westminster Abbey, which obviously made a great impression on the artist.

Hymn Book: It is open at the page that contains the hymns, ’The Ten Commandments’ and ‘Come, Holy Ghost’. They are the German translation by Martin Luther. This could be a plea by Holbein for reform of the Church along Protestant lines, but without alienating the Catholics.

Lute: The lute is a symbol of harmony, but it has a broken string symbolising the growing animosity between Protestants and Catholics.

Book: Georges de Selve’s arm rests on a book on the edge of which is written in Latin, ‘his age is 25’

Sundial: It reads 11 April 1533. During Easter of 1533 Henry VIII broke away from the Catholic Church and established the Church of England.

The Ambassadors mission was to try to persuade Henry VIII not to break with Rome and also to protect French interests and influence – a difficult mission that ultimately failed. The picture was painted in London.

In the 19th century artists used symbols in a much more obscure way in an attempt to give their work a mystical or spiritual feel. These paintings appealed more to the emotions and came close to having a dream-like quality. The work of Gustave Moreau is a typical example. Such paintings were known as Symbolist paintings and proved to be a vital inspiration for the Surrealist painters of the 20th century.

Really Obscure Symbols

As we have seen with the more traditional signs it is possible to read’ any work of art if you know the code, or literal meaning of the symbols. However, understanding content in art becomes really hard when artists use symbols in a more obscure way by applying parody, metaphor or irony. This is because each artist, being an individual, and will apply these elements differently. Therefore, below is just an outline guide.

Parody

In parody we mimic the appearance or manner of something or someone, generally with a twist for comic effect or critical comment. The Young British Artist (YBA) Mark Wallinger often uses parody in his work an example would be, Behind You – Oh no he is, Oh no he isn’t 1993 (a pantomime horse with its bottom in the air)

Metaphor

The artist will sometimes make use of metaphor to bring to mind an idea or meaning that is not actually represented by the object.

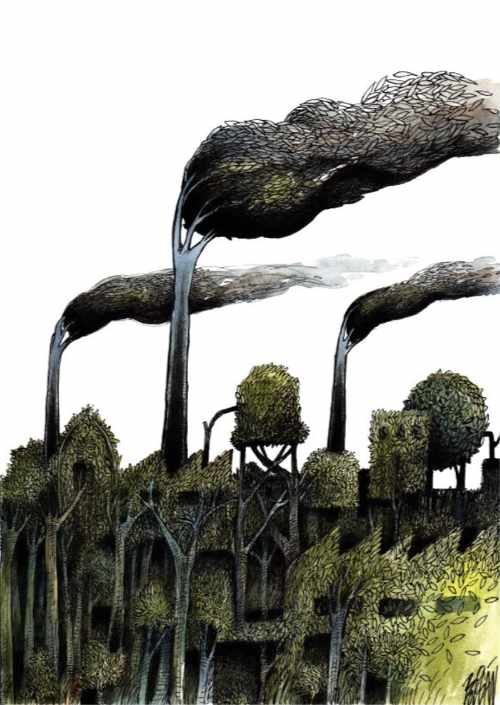

Irony

The artist sometimes makes great use of irony, the ability to twist or completely reverse the apparent meaning. We can see this in this illustration of trees by Cuban artist Angel Boligan. However, some say that art critics use irony more than artists do, especially when talking about contemporary art, the unkind say it is simply a means of disguising the fact they have no idea what artists are trying to say.