Artist Profile

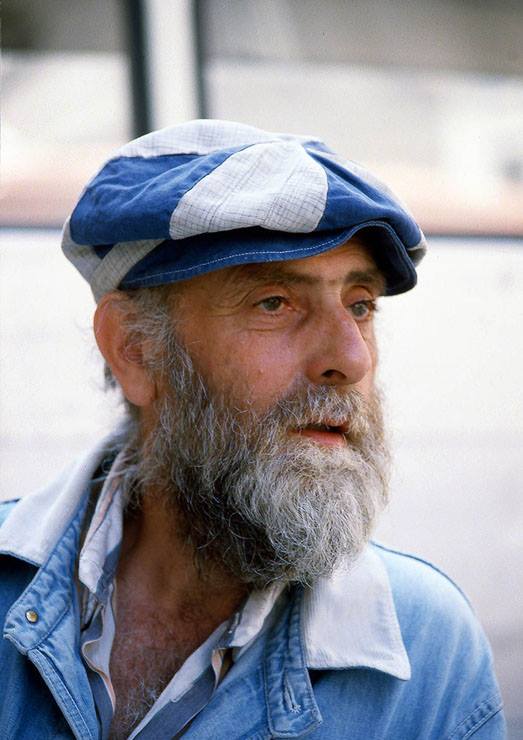

Friedensreich

Hunderwasser

Born – 15 December 1928 – Vienna, Austria

Died – 19 February 2000 – Queensland, Australia

Artist Profile

Friedensreich Hundertwasser

Born – 15 December 1928 – Vienna, Austria

Died – 19 February 2000 – Queensland, Australia

Friedensreich Hundertwasser, one of the most unique and groundbreaking artists and architects of the 20th century. Hundertwasser’s work is a symbol of creativity, individuality, harmony mixed with an ecological passion which is what makes this artist so very interesting.

Hundertwasser’s Early Life

Friedrich Stowasser, later known as Hundertwasser was born on December 15, 1928, in Vienna, Austria, to Ernst Stowasser, a technical civil servant and former officer from World War I, who was a catholic and Elsa Scheuer, who was Jewish. Tragically, his father passed away when Friedrich was just two years old. Friedrich was baptised in 1935 and from 1936 to 1937, he attended the Montessori School in Vienna. In 1938, after the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany, he and his mother moved in with his aunt and grandmother. It was a time of intense political and personal turmoil. His mother, Elsa, faced unimaginable challenges during the Nazi era primarily because the family were Jewish. It was therefore vitally important to stay inconspicuous so as to avoid persecution. As a result, they pretended to be Catholic and young Fireidrich even joined the Hitler Youth. But the horrors of the war caught up with the family in 1943, when 69 of his maternal relatives including his grandmother and aunt were rounded up and deported to Nazi concentration camps where they were subsequently gassed. Stowasser and his mother survived the holocaust by living hidden in a basement in Vienna for the remainder of the war.

Hundertwasser’s early art education

After the war in 1948, Stowasser briefly studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna under Professor Robin Christian Andersen. However, after just three months, he left, rejecting formal education in favour of developing his own artistic style, which was much influenced at the time by the exhibitions he saw featuring Walter Kaufmann and Egon Schiele. This period marked the beginning of his life as an independent, self-taught artist who was determined to challenge the conventional norms of the art world.

In 1949, Stowasser began an extensive journey through Europe, particularly to Italy and France. It was during this period that he adopted the name “Hundertwasser.” His adopted surname was based on the translation of “sto” (the Slavic word for “one hundred”) into German. The name Friedensreich has a double meaning either “Peace-realm” or “Peace-rich”. Therefore, his new name Friedensreich Hundertwasser translates directly into English as “Peace-Realm Hundred-Water”.

In 1950, he stayed in Paris, very briefly attending the École des Beaux-Arts. He left on the first day. That same year, he met René Brô, a French artist, and the two painted murals together in Saint Mandé.

Hundertwasser’s ideas begin to develop

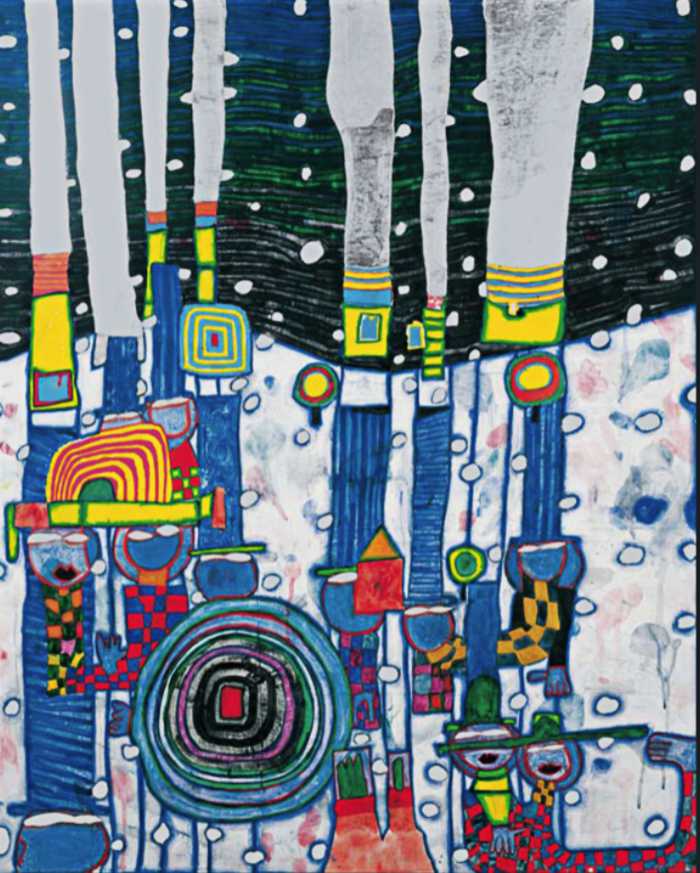

By 1952, Hundertwasser gained some national recognition, when he had his first exhibition at the Vienna Art Club which he had joined the previous year. His work could be described as decorative abstract, but as he delved deeper into his own philosophy, it began to take on more distinct characteristics, with his use of bright, naturalistic colours, swirling organic forms and spirals. He completely rejected linear perspective and straight lines which he believed were “godless” and “immoral.” His inspiration at this time, were artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Marc Chagall, and Paul Klee.

In 1954 he had his first exhibition in Paris at the Studio Paul Facchetti. Later in September and October of that year he was admitted to hospital in Rome and treated for jaundice. It was here he painted numerous watercolours and around this time, he also developed his theory of trans-automatism which focused more on the experiences of the viewer rather than the artist himself. It was also based on his belief that humans had lost their connection to the organic geometry of nature by forcing themselves to exist in boxes as homes. He believed the fluidity of line and shape seen in nature should form the basis of his own architectural and painting style.

Hundertwasser’s attack on modern architecture begins

In 1957, Hundertwasser published his Mouldiness Manifesto in Seckau, Austria. This criticised modernist architecture and advocated a more organic, nature-integrated design. This manifesto marked the start of his lifelong critique of modern architecture, which he saw as sterile and unnatural. During this time at symposiums and lectures, he would made bold statements championing the idea that architecture should be a free, creative practice. To emphasise his ideas, he often wore mismatched socks to ridicule the idea of symmetry. In the same year he bought a farmhouse in Normandy, France and published the pamphlet, ‘The Grammar of Seeing’ in Paris.

In 1958 Hundertwasser married Herta Leitner in Gibraltar, but the marriage only lasted two years.

In 1961 he held a successful exhibition in Tokyo, Japan and in 1962 married the Japanese artist Yuko Ikewada, but they divorced later in 1966. The early 1960s saw Hundertwasser gain international recognition, by exhibiting in Japan, the United States and across Europe. His radical approach to both art and architecture began to capture the imagination of the world. The architectural sketches and models he produced at this time outlined his ideas for what he called ‘healing architecture’, through which he sought to promote an ecological way of living.

Hundertwasser’s healing architecture

His ideas for ‘healing architecture’ eventually came to fruition in 1983 when the Austrian federal chancellor and the mayor of Vienna, who both supported his vision, granted him the opportunity to realise his ideas in Vienna with, what became known as, the Hundertwasserhaus. It was an apartment complex that epitomised his philosophy of organic, nature-integrated architecture. The building, completed in 1985, became one of his most famous works—complete with uneven floors, curving walls, and trees that grew out of windows. It is a testament to his belief that buildings should resemble living organisms, not sterile, geometric structures. As he often said, “A house is not a house, it is a tree.”

1967 and 1968 saw Hundertwasser deliver his famous “Naked” speeches in Munich and Vienna. They were a kind of manifesto of his ideas at the time. He stood in front of his audience naked, the idea being that a human being had three “skins:” the epidermis, the clothing, and the dwelling place. He took it as a sacred right that a human being should be able to express his individuality in all three skins, especially in the exterior of his living space, instead of being consigned to an anonymous box.

Hundertwasser’s Printmaking developments

In 1969 he created the graphic work 686 Good Morning City – Bleeding Town in 120 colour variations in a print run of about 10,000. He used completely new techniques to create the prints including metallic-stamp printing, phosphorescent colours that glowed in the dark, appliqués of reflecting glass-beads, and an incredible number of colour overprints which he painted separately on transparent foil, before transferring them to the screen for printing. It was a two-year project that eventually led to take court action against his printers. He wanted to fix the price of his prints to make them as assessable to as many people as possible, but with demand very high prices were driven upwards. He won the case, and the price was fixed at 100 marks per print. But as he said later, ‘it was all for nought, I could not fix the price on the open market. It was a victory and defeat all in one.’

In 1971 he began work on the designs for the 1972 Munich Olympic poster. Also, that year he bought a dilapidated ship, the Regentag (“Rainy Day”), which he renovated and converted into a floating home and studio in the dockyards of the lagoon in Venice. In 1972 his film ‘Rainy Day’ about the renovation was shown at the Cannes Film festival.

During 1973 and 1974 he produced his first Japanese woodcuts, had a travelling exhibition which was shown in various museums in Australia and had an exhibition in New York. He also sailed the Regentag to Tunisa, Cyprus and Isreal and visited New Zealand,

Hundertwasser buys properties in New Zealand

Following his visit to the south seas he bought several properties in the Bay of Islands in New Zealand including the entire Kaurinui Valley. He wanted to give the land back to nature and during the rest of his life planted more than 100,000 native trees, built canals, ponds, and constructed wetlands there. He also used solar power and water energy from a water wheel and constructed humus toilets in all his houses.

In 1981 he was appointed Head of a Masterschool for painting at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. Later in 1982, Hundertwasser’s only child, his daughter Heidi Trimmel, was born but Hundertwasser had little contact with her. Also, in 1982 he painted ‘Island in the Yellow Sea’. It is a clear reflection of Hundertwasser’s obsession with spirals as a symbol of life’s cyclical nature. In this work, the spiral motif dominates the composition, drawing the viewer’s eye into the swirling colours suggesting the eternal, interconnected flow of nature and life.

The Spittelau Waste Incinerator Plant

In 1988, the mayor of Vienna commissioned Hundertwasser to redesign the Spittelau waste incinerator after it had burned down in 1987. Hundertwasser turned it from an industrially functional building into a monumental work of art that is visible from all corners of the Austrian capital. Inaugurated in 1992, the incinerator plant, still integral to Vienna’s waste management system, transforms the energy of household waste into heat for more than 60,000 households a year. The beautification of a waste incinerator might be seen as a ‘greenwashing’ the waste-dependent society that Hundertwasser was opposed to. But he decided to take on the commission because of the energy production capacity of the plant and its contribution to urban sustainability.

Hundertwasser’s postage stamp designs

In 1991Liechenstein commissioned Hundertwasser to design a commemorative postage stamp and to co-ordinate the Homage to Liechenstein stamp series in which other artists also contributed designs.

Throughout the 1990s, Hundertwasser continued to work on many architectural projects in Japan, Germany, New Zealand and Austria. Two examples being the Tokyo 21st Century Clock Monument which was designed to stop when the turn of the century was reached and the thermal spa in Bad Blumau, Austria which was completed 1998. Also, that year he created the Hundertwasser Toilets in Kawakawa, New Zealand, which is now a famous tourist destination.

Throughout his life Hundertwasser continued to paint, he never had a studio or an easel but would spread the canvas or paper flat out in front of him. He made many of the paints himself and constantly experimented with different techniques and materials. On most of his paintings he would note on the back when and where they were painted. With this the painting, ‘The Four Antipodes’ of 1999 we know the painting was produced at Kaurinui, New Zealand between January and March and was created using mixed media including, watercolour, egg tempera, oil and laquer on primed paper that was glued to canvas.

Hundertwasser’s final years

In 1997 he was awarded the Grand Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria and had a museums exhibition tour in Japan in 1999. But on the 19 February 2000, Friedensreich Hundertwasser passed away from a heart attack on board the Queen Elizabeth 2, whilst travelling in the Pacific Ocean. In accordance with his wishes he was buried in New Zealand, in the Garden of the Happy Dead beneath a tulip tree. There is no gravestone but perhaps his wishes are best summed up by what he wrote in 1979. ‘I am looking forward to becoming humus myself buried without a coffin under a tree on my land in Ao Tea Roa.

Hundertwasser’s life was a remarkable journey through adversity, creativity, and a deep commitment to the natural world. His extensive body of work included hundreds of paintings, numerous architectural projects, and over 26 postage stamps designs. His bold vision of integrating nature into art and architecture led to the creation of not only his iconic Hundertwasserhaus in Vienna, but also to a unique contribution to sustainable architecture. He demonstrated quite uniquely that art and nature can have a positive, transformative and environmental impact on the way we all live our lives.

RELATED VIDEOS

Paul Klee

Marc Chagall

Wassily Kandinsky

Artwork

Leave A Comment