An Outline of the Movement

What Futurism Means

The story behind the Movement

What Futurism Means

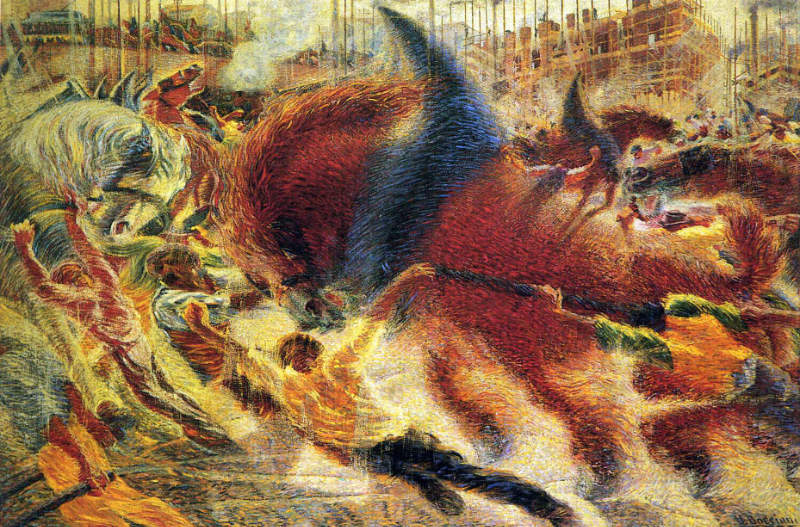

Futurism developed during the first decade of the 20th-century as an essentially Italian movement ‘Futurismo’. It also grew prominently in Russia. It’s primary focus was an emphasis on dynamism, (‘absolute motion + relative motion = dynamism’, F. T. Marinetti’). It was inspired by speed, energy, and the power of the machine and the vitality, change, and restlessness of modern life in general.

Manifestos

Futurism was first announced on 20 February 1909, when Le Figaro published a manifesto by the Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. The name Futurism was coined by Marinetti. The movement reflected his emphasis on getting rid of the ‘static and irrelevant art’ of the past. He wanted to celebrate change, originality, and innovation in both culture and society.

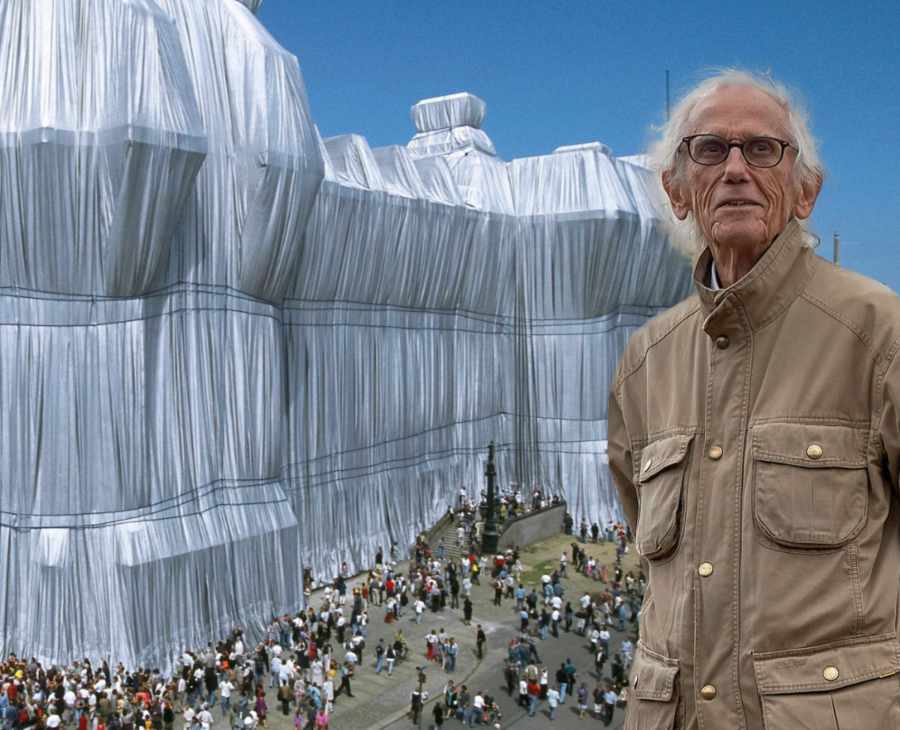

Umberto Boccioni – The City Rises 1911

Marinetti’s manifesto glorified the new technology of the car and the beauty of its speed, power, and movement. He exalted violence and conflict and called for the sweeping rejection of traditional cultural, social, and political values. He also advocated the destruction of such cultural institutions as museums and libraries. The manifesto’s rhetoric was passionately bombastic. Its tone was inflammatory and purposely designed to inspire public anger and attract widespread attention.

‘We will sing of great crowds excited by work, by pleasure, and by riot. Sing of the multicoloured, polyphonic tides of revolution in the modern capitals. We shall sing of the vibrant nightly fervour of arsenals and shipyards blazing with violent electric moons. Greedy railway stations that devour smoke-plumed serpents and factories hung on clouds by the crooked lines of their smoke. Bridges that stride the rivers like giant gymnasts, flashing in the sun with a glitter of knives. We admire adventurous steamers that sniff the horizon. And deep-chested locomotives whose wheels paw the tracks like the hooves of enormous steel horses bridled by tubing. We love the sleek flight of planes whose propellers chatter in the wind like banners and seem to cheer like an enthusiastic crowd.’

Excerpt from the ‘Manifesto of Futurism’, by F.T. Marinetti 1909.

What did Futurism Want?

Futurism lacked a defined visual style and is often overlooked as an odd off shoot of Cubism. But like Symbolism before it, it was more interested in ideas than style. It challenged traditional artistic values, and the aesthetic ambitions of much of the art world. Its numerous manifestos are filled with theories of speed and dynamism. Futurism insisted that the growth of technological change demanded expression in new bold art forms. This idea was not original, but it had never been expressed so forcibly before. It is also important to realise that Futurism appeared in Italy with its rich Renaissance heritage. Perhaps, it was a rebellion against a society that was ‘timeless’ and predominantly rural. Unlike most of the rest of Europe.

Futurist life was essentially urban, and inspired by the industrial cities of Northern Italy. Yet the futurists criticised these cities, dismissing them irreverently as ‘museum cities’. It was some time before the Futurists found an architect sympathetic to their views and visions.

Antonio Sant’Elia, signed the “Manifesto of Futurist Architecture” in 1914, the year he met Marinetti. He proposed that the modern city should be the backdrop against which the dynamism of Futurist life should be lived. All of Sant’Elia’s projects were simply visionary. Surprisingly, no futurist buildings were ever built.

Sant’Elia stressed his work was not just utilitarian architecture, but an art form in which lines were dynamic, oblique and elliptical. In rejecting nature as an inspiration, he wanted architecture to be the ‘most beautiful expression of the mechanical world.’

The Influence of Futurism

There is no doubting Futurism exerted a powerful influence on the art world in the early part of 20th century. Their worship of the machine and technology as the solution of all social ills, would influence the Russian Constructivists. The Futurist’s creation of sound poems, nonsense verse and pamphleteering was adopted by the Dadaist movement and become commonplace for lots of political parties. Futurism was also a highly motivated form of theatre, influencing Vladimir Mayakovsky and inspiring Antonin Artard’s, ‘Theatre of the Absurd’.

The First World War, ‘the world’s only hygiene,’ as Marinetti called it, brought the Futurist movement to an abrupt end. After the war the remaining Futurists – Boccioni and Sant’Elia were killed in 1916 – adopted more conventional artistic styles. Marinetti, unsurprisingly, helped to establish the Fascist movement in Italy.

Check out the article on Fauvism